no description

no description

It was an athletic tragedy that hit home with equal impact on the Penn State campus and in the State College community. No, it wasn’t a defeat in the win-loss column; it was a death suffered by a track and field competitor.

On Feb. 23, 2002, 15 years ago today, Kevin Dare suffered a fatal accident during the Big 10 Indoor Track and Field Championships in Minneapolis. Something went wrong near the top of Dare’s first jump — an attempt at 15 feet, 7 inches — and he lacked the momentum to carry him onto the landing area. He plummeted downward without clearing the bar, and he struck his head on the metal box where the jumpers plant their poles. The magnificent young life of Kevin Dare had ended much too early at age 19.

“‘Unbelievable is the word that comes to mind,” recalls Kevin’s roommate and fellow Penn State pole vaulter, Dave Bollinger. “You’re thinking, ‘It’s bad, it’s going to be a long recovery,’ but never in a million years would you think it would be death.”

But the reality was worse than a nightmare — for Bollinger, the person who was standing the closest to where Kevin fell, and for Kevin’s parents, watching from the stands. Meanwhile, Kevin’s older brother, Eric, had remained in State College and soon got the most shocking news of his life.

“My phone was blowing up,” says Eric Dare. “The captain of the track team was calling me, and other guys from the team were calling me, and they were leaving messages like, ‘Your brother got hurt, and it’s not good.’ I immediately started to panic, but I couldn’t get through to my parents. Finally, my dad called me and gave me the news. He just said, ‘We lost Kevin,’ and it took every ounce of strength for him to get those words out. I just remember breaking down in tears and saying, ‘No, that can’t be possible!’ “

A FINAL HUG

Eric had seen his brother just two days earlier when Kevin boarded the team bus outside Penn State’s track complex. Eric, a varsity football player and javelin thrower, was working out at the facility to prepare for the outdoor season. “I had this weird feeling,” he remembers, “that even though I had already said goodbye to him that morning, that I should go and give him a hug. So I gave him a hug, told him I loved him and said, ‘Good luck, man.’ And that was the last time I saw him.”

Today, Eric remembers his brother as an “incredible athlete” and does not doubt that Kevin could have reached his goal of competing in the Olympic Games. Indeed, Kevin had captured the Pennsylvania high school title as a State High pole vaulter in 2000; then he won the U.S. National Junior Championship in 2001 and competed for the U.S. in the Pan American Junior Championships. All the while, he remained largely unaffected by the plaudits or expectations of others. Once, recalls Eric, when he won a major event sponsored by Nike, “Kevin gets up on the podium and he’s decked out in Adidas. But he didn’t care — that was his outfit, it was his uniform. He was the Nike Indoor All American champ and he’s rocking Adidas.”

Eric, just 14 months older than Kevin, enjoyed a front-row seat to observe his brother’s short but sensational life. “He was a fun guy to be around,” says Eric. “He was always the life of the party. The girls loved him. And the one thing that stood out about him was his integrity. He wouldn’t always tell you what you wanted to hear, but you knew he was never going to lie to you.”

Bollinger, perhaps Kevin’s closest friend at Penn State, offers similar observations. “He was a natural leader,” says the former vaulter from Lancaster County. “He was fun-loving, charismatic, everybody was drawn to him.”

And as for the matter of integrity, Kevin’s former roommate puts it this way: “He didn’t care who he was up against. If there was something he thought was right or wrong, he wasn’t going to waver from that because of somebody in a position of power.”

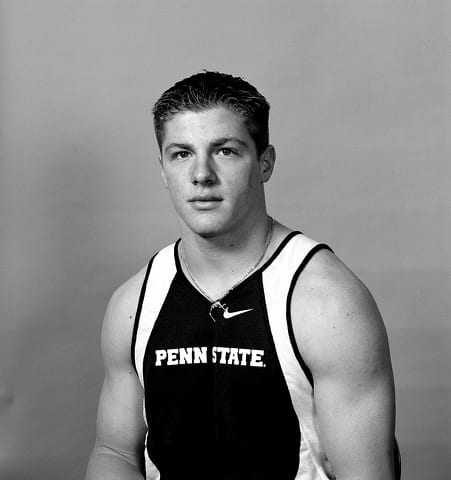

Kevin Dare pictured in his Penn State track and field media guide photo. Image courtesy Penn State Athletics.

* * *

So what do you do when you lose someone as young and special as Kevin? I’m sure there is no one-size-fits-all answer, but I know what Ed and Terri Dare chose to do. Rather than drown in an ocean of sadness, the parents channeled their grief into efforts to help others. Although I’ve never met Ed and Terri, I’ve known Ed’s former business partner, Bob McNichol, for more than 30 years, and I’ve seen Bob’s respect for the couple and their surviving son.

Says McNichol, “The Dares, including Eric, have been tremendously courageous in turning their heartache into doing everything they can so the same thing doesn’t happen to other young athletes.’

In addition to supporting other charitable causes through the Kevin Dare Foundation, the Dares spent more than 10 years in working to reduce pole vaulting’s dangers. “Certainly we’ve made tremendous strides,” says Eric. “On a scale of 1 to 10, it’s probably a 6 right now. There’s a lot of room for improvement, but it’s better than when my brother did it. Then, it was probably a 3.”

Indeed, things could not have been much worse than they were in the early months of 2002. Not only did Kevin lose his life then, but so did two high school vaulters. Just a week after Kevin’s death, Ed said this to a New York Times writer: “I feel the safety behind pole vaulting is tremendously outdated. It’s the one event in track and field that has changed the least while performances have gone through the roof.”

And so the Dares, aided by many State College and Penn State friends, went to work. They raised money, hired experts, lobbied coaches, administrators and politicians. No doubt, their greatest achievement was in the design and adoption of the “soft box” landing area. As one vaulting coach said just a few years ago, ‘They’ve padded everything that can be padded. It has had a clear effect in reducing injuries.”

But then there’s the matter of wearing helmets. Despite extensive research and the design of a special helmet for pole vaulting, it is rare to see a jumper wearing head protection. Although Eric believes that helmets have great potential for reducing catastrophic injuries, he chooses not to criticize the younger athletes who compete without them.

“When Kevin was a freshman at Penn State,” says Eric, “we were watching a meet and there was one kid who had a helmet on. And Kevin said, ‘Oh, he’s probably just afraid of getting hurt.’ That was the mentality — ‘It doesn’t look cool’ or ‘They’re just afraid.’ “

The Dares clearly are not against pole vaulting. In fact, notes Eric, “We love the sport.” But they also believe it is vital that competitors and their parents are educated on the risks, that coaches encourage or require helmet use and that elite pole vaulters provide the right example for young jumpers.

“I am very disappointed that these athletes are not using the helmets that are now certified by ASTM standards and invented specifically for pole vaulting,” says Eric. “Kevin was the type of leader who would have worn a helmet no matter how uncool it was considered if he had known the real dangers of the sport. He would have wanted to serve as a role model for others. Many of the best athletes in the world who fly through the air — snowboarders and skateboarders like Shaun White — wear helmets, and no one ever thinks they are less than cool.”

* * *

Eric Dare has lived a lot of life since his beloved brother passed away. He’s graduated from Penn State, gotten married (to the former Caitlin Pezalski from Boalsburg), become the father of three (with a fourth baby coming soon) and joined his father in the leadership of several investment companies. But his memories of Kevin’s life have never dimmed, and the questions sparked by Kevin’s death have never been answered.

MUSIC RECALLS MEMORIES

As for the memories, if Eric hears a certain song, he can immediately picture himself at State High’s vaulting facility nearly 20 years ago.

“When I would get done with javelin practice,” he says, “I would go up on the bleachers and watch Kevin and his friends jump for another hour or hour and a half. They would take their cars out there, turn on a radio and practice.”

Their favorite song, predictably enough, was “Jump” by Van Halen.

And then there was the PIAA championship meet won by Kevin in 2000. It was a horrible day for jumping — cold and rainy — and Kevin was locked in a three-way tie at 14 feet, 9 inches with an Altoona athlete and with his future buddy, Dave Bollinger. A jump-off was needed to determine the winner, and only Kevin was able to clear that height. “We were all ecstatic and proud as a peacock for him,” recalls Eric. “Hey, that’s your brother up there, and he’s a state champ.”

As for the questions, Eric admits he’s still puzzled about the death of his brother at the age of 19. “I’ve spent many nights wondering about that. The Billy Joel song, ‘Only the Good Die Young,’ I hated that song for so many years after he died. I’ve wondered over the ‘why’ question so many times, and I just accept that some day I’ll hopefully find the answer.

“The hardest part for me right now is that I’m raising my own family. My wife and I talk about my brother as if he’s still here. And my kids, they talk about their Uncle Kevin and they’ve never even met him. Last night, my son who’s named after him — he’s only three years old — came up to me with no reason and said, ‘Dad, I miss Uncle Kevin.’”

SUPPORT FROM TOWN & GOWN

But when you ask Eric about the support his family has received, that’s a question which is much easier for him to answer.

“First and foremost,” he says, “would be [former Penn State athletic director] Tim Curley. The day my brother died, he picked up the phone, offered his condolences and said he would do anything he could to help us. And that man literally did that from hour number one. He helped us with inventing helmets, the soft box, getting us in front of expert scientists, helping us create an endowed scholarship at the university in Kevin’s name. He certainly was a partner.

“And a lot of community members volunteered their time to help us raise money. It’s the beauty of living in State College. When Kevin died, we had meals for weeks. People we’d never even met were stopping by our house and saying, ‘We’re so sorry. You don’t know us, but we just wanted to do something for you.’ This community has been scarred in recent years, but there are a lot of great people here. And that’s what we experienced when our tragedy hit.”

Eric is not one to deny the pain that he and his parents have felt since Feb. 23, 2002, but he also beams when asked to describe Kevin’s continuing legacy.

“Kevin, for his 19 years,” says Eric, “made an impact on so many people. Even after all these years, I could list a handful of friends who would say, ‘Kevin Dare’ if you asked them, ‘Who is the one person who impacted your life the most?’”

Receive all the latest news and events right to your inbox.

80% of consumers turn to directories with reviews to find a local business.