This story originally appeared in the November 2025 issue of Town&Gown magazine.

Over the course of 42 years, Ron and Tammy Chronister have fostered approximately 80 children. Now, at 69 and 66 years old, respectively, the two are adoptive parents to five children ranging in age from 2-1/2 to 38. Four of the children currently live with the Chronisters, while their eldest, 38-year-old Sara, resides in Osceola Mills.

Benevolence has always been associated with the Chronisters, so it always stung Ron when he couldn’t share one of the most meaningful elements of his life with his foster children. Ron had routinely hunted with his father and uncle when he was younger, and it remains an essential part of his life. Commonwealth laws, though, prohibit foster parents from hunting with their foster children.

Those restrictions, however, drop once a child is adopted.

One of Ron’s most cherished moments formed last year when his then-10-year-old adopted son, Cooper, secured his first turkey.

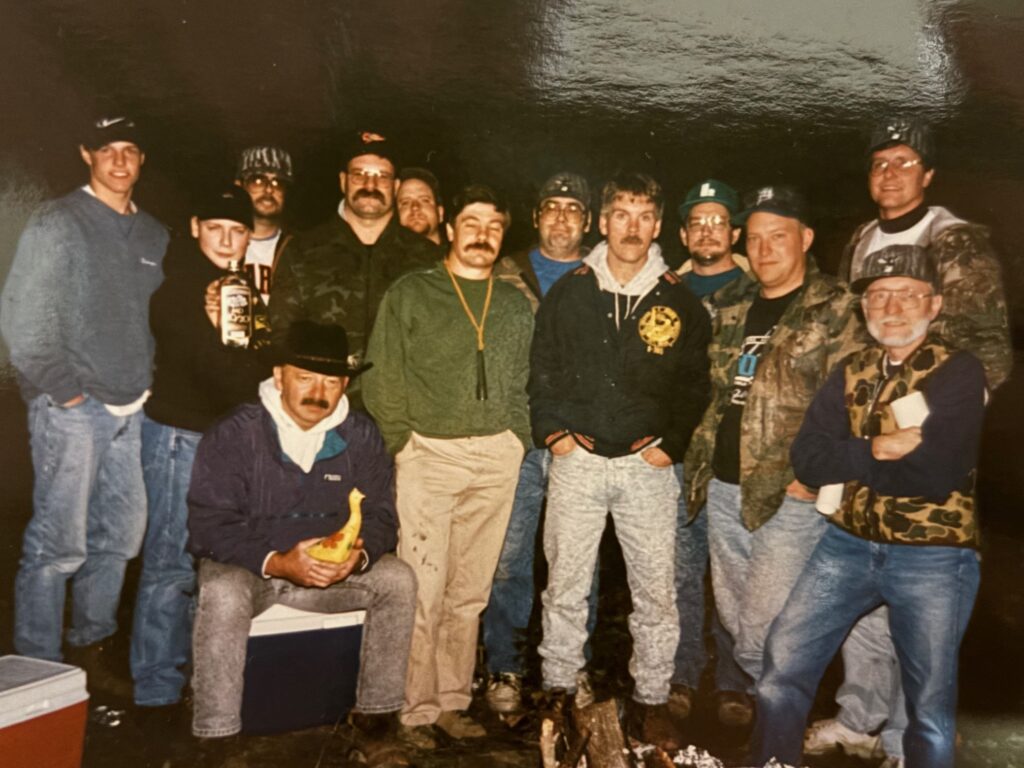

“I took him when he was 10, as a mentor, and he got his first fall bird,” Ron says. “Oh, boy. We went back to the hunting cabin, and all the guys were back there congratulating him. … We started laughing and took pictures.”

Ron was born in Bellefonte and later moved to Zion. He keenly recalls hunting with his father and uncle during his earlier years, which invigorated his zeal for the sport. During his adult years, Ron became even more entrenched in hunting when he teamed up with Greg Caldwell of the now-defunct River Valley Game Calls, and later became part owner of the company. An avid turkey hunter at the time, Ron was renowned for crafting turkey calls.

“We made turkey calls, deer calls, crow calls; we kind of did it all,” he says.

Ron enlisted the help of Tammy and the children at the time to assist with the call-making process.

While last year’s hunting memory of Cooper recording his first turkey remains one of his favorites, an experience he shared with his daughter Marlena a few years ago ranks among his dearest.

Marlena was 10 at the time and, armed with her mentor’s license, joined her father on their first hunting venture. As the two waited patiently in their hunting blind, father gave the youngster a directive to watch for deer. Taking the command literally, Marlena stood upright from her chair, walked over to the window and stuck her head out of it in search of the animal — a cardinal sin in the hunting community.

“I told her, ‘No, no, no! Just look out the window — you don’t have to move,’” Ron recalls. “We laughed about it. It was pretty cool. Things like that I’ll never forget.”

Marlena’s entry into hunting didn’t extend too much beyond that. According to Ron, one of its requirements didn’t quite appeal to her.

“She’s not into it,” he says with a laugh. “I don’t think she too much cares for the way we harvest the animals.”

The allure of hunting once gripped the Chronisters’ oldest daughter, Sara, but the responsibilities of motherhood have kept her away. A love for hunting has found its way to her children, though, further ensuring that the activity Ron inherited from his father and uncle will remain in the family for at least another generation.

“It’s great,” Ron says of his grandchildren’s passion for hunting. “The way I see statistics, and the long run, [hunting] seems like it’s dying off. Just like Doc [Greg Caldwell] told me, a lot of people are against hunting, but if there wasn’t hunting, you’d have to lead the deer across the road because there would be herds of them. You’d see turkeys flying into your windshield or coming into your yard.”

History revisited

Julian resident Jacob Weston vividly remembers accompanying his father, Kevin, on a particular hunting venture on state game lands when he was around 6 or 7 years old. As the pair navigated the paths through vegetation, Kevin suddenly stopped walking.

Jacob followed his father’s lead, wondering why he stopped suddenly. The reason soon became clear when Jacob spotted a black bear approaching. Jacob, now 40, looks back and jokingly says the bear seemed much bigger back then.

“It wasn’t very big,” Jacob recalls. “To a 6- or 7-year-old, it was a pretty good size. Looking back on it, it was probably just a little bear.”

In Jacob’s younger years, hunting was a staple in his family. His grandfather, Earl, would join his son and grandson whenever the trio had an opportunity. They’d seek just about anything that was available, including deer, turkey, squirrel, rabbit, and bear.

“My grandparents were in their 40s when my dad was born,” Jacob says. “At that point in my pap’s life, everything revolved around hunting. He had his life set up for that. So that’s how my dad got into it so big. And then when I came along, I got into it really big. But my pap, he loved hunting turkeys. That was his thing.”

Turkey hunting in the fall coincided with another one of Earl’s passions: Penn State football. The timing of fall turkey season prevented him from watching the games on television on Saturdays, but that didn’t stop him from following the Nittany Lions.

“He would carry a little radio,” Jacob says. “We’d walk a little while, and he’d turn the radio on to catch the score of the Penn State game. We’d listen to it until they gave a score. We’d turn it off and move to a different spot and do the same thing all over again.”

Earl’s allegiance to the Nittany Lions helped his grandson deconstruct one of hunting’s most widely held beliefs.

“This is the part that drove me nuts because I thought with hunting that I had to be quiet,” Jacob says with a chuckle. “It was preached to me that I had to be quiet.”

Jacob and his wife, Brandi, are parents to four children — three girls and one boy. Six years ago, while hunting on state game lands with his now 14-year-old son, history repeated itself when Jacob spotted a small black bear walking toward them. Over the years, he had shared his childhood bear story with his son, so seeing it unfold again was surreal.

“I let it get closer to him and me than my dad let that other one get to him and me,” Jacob says. “[My son] was about 8 when that bear came over the hill toward us.”

Preserving the importance

Neil Henry has one of the more unique experiences to mark one’s hunting beginnings.

As a 12-year-old hunting for the first time, Neil, accompanied by his father, Gary, killed a deer during the first day of hunting season — a feat uncommon for first-time hunters. His father’s response still remains vivid after 30 years.

“I had been tracking deer with him and his friends numerous times before, and his reaction to me getting my deer was far more exciting than any of his own or his friends,” Neil, now 44, says.

Neil killed his first buck a year later in another stroke of hunting good fortune. He and his father harvested the buck, a memory he holds in high regard, but it was the reaction from his grandfather, Richard Barger, that sticks the most with Neil. Richard had stayed behind in the family’s cabin at their property in the Allegheny National Forest that afternoon while his son and grandson set out for bounty.

“At that point, my grandfather’s health was starting to go downhill, and he didn’t go out in the woods for the whole day,” Neil explains.

When Neil and his father returned to the cabin, the youngster’s grandfather and two uncles joined for a photo with the prized buck. Although Richard has passed away, the photo taken that afternoon ensures that Neil will never forget the memory.

“He was so excited and so proud,” Neil says. “That picture that we have of us with that deer, he’s almost front row and center, almost blocking the entire view. … I was his oldest grandson, so I would have been his first grandson to be up there, and he was the originator of the camp, so it was definitely a proud moment for him.”

Now, as a father of three, Neil is doing his part to create family hunting traditions and the accompanying memories. His 12-year-old daughter and 8-year-old son have already taken to it. His wife, Laurie, secured her hunting license this year after a hiatus. She plans to join the others on their hunts.

While the meat such hunts yield is appreciated and welcomed, Neil, who lives in Bellefonte, says he’s establishing a respect for hunting and its ecosystem with his children, the same way his grandfather and father did with him years ago.

“More than anything, it’s about teaching them respect for the outdoors, teaching them that the only goal of hunting is not just harvesting an animal,” he says. “It’s an escape — especially these days — from electronics and the busyness of life. Just getting them to appreciate the outdoors.”

Fo(u)r generations (and more)

There was zero chance the hunting bug would escape Penns Valley resident Ty Corl.

Ty’s parents, Sherri and Terry, enjoyed the sport, the byproduct of watching their fathers hunt in their early years. So just before Ty’s 12th birthday, he joined the ranks and set out on his first hunting adventure with his father. And although the youngster couldn’t carry a firearm at the time, it didn’t stop him from enjoying those outings.

The extended Corl family includes four generations of hunters. Ty’s grandfathers, Neal Corl and Monty Strouse, both octogenarians, still make it out today.

“He hunts what used to be our farm, and it was sold, so now he just goes out every once in a while when he feels like it,” Ty says of Neal. “He puts in a good first week [of the season]. He usually still goes by himself.”

Monty has hunted for nearly seven decades. These days, he says his availability to hunt depends on what’s in season. Now 81, he first started hunting in his native Clinton County when he was 12. His father, Richard, would accompany him. His grandfathers and uncles were avid hunters, too.

“Lots of memories,” Monty recalls of hunting with his father. “Turkey hunting, deer hunting, bear hunting. We hunted every chance we got until I got old enough to go by myself after school with a couple friends.”

A few years ago, Ty convinced his niece to join him on one of his hunting excursions not long after her 12th birthday. She was hesitant about hunting but respected her uncle’s opinion enough to give it a chance.

Unknown to her, Ty had spent the previous three years tracking a buck that always seemed to elude him. She proved the lucky charm that day and they got the buck, which ultimately ignited her passion for hunting.

For now, hunting appears to be staying in the family for at least another generation. As a result, it further preserves a family tradition that remains a cornerstone in so many lives.

“I took her out the first morning of rifle [season], and I ended up shooting that buck that I was after,” Ty, 35, says. “That kind of hooked her, so she got her hunting license. Last year, she killed her first doe.” T&G

Elton Hayes is a freelance writer in State College.