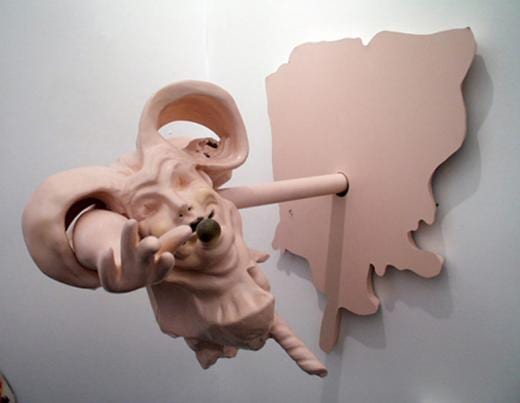

Name: Bonnie Susan Collura

Position: Assistant Professor of Art, School of Visual Arts

Education: M.F.A. (sculpture), Yale University, 1996; BFA, Virginia Commonwealth University, 1994

Links: School of Visual Arts bio

Samples of work on Flickr.com

The Prince Project at AbsoluteArts.com

First show at Lehmann Maupin

What do you teach?

Currently I teach Graduate Seminar and new class called Digital Hand, which merges analog building materials with CAD software and hardware. I also teach Beginning Sculpture, Advanced Sculpture, Intermediate Sculpture (that focused on various welding applications), and a class called Issues of the Body that deals with the body in space as it related to politics, persona, performance, and culture.

Where are originally from and how did you get to Penn State?

Well, since I was a child, I have moved 18 times, so I rarely feel like I am from any one place. However, before moving to Central Pennsylvania, I lived in Brooklyn, New York for 10 years. New York’s pace, diversity, and endless spectacle feel symbiotic of many aspects of my personality, so I do feel like I am “from” New York. I got to Penn State by applying for the sculpture position listed about three years ago. Here I am!

How did you get interested in sculpture?

Well, this is a good question. When I went to VCU for undergrad, all of the art students had to take foundation classes before declaring a hopeful major. One of my foundation teachers was Elizabeth King. She was full of energy, a wealth of information, and a little bit wacky. I liked being around her and, more importantly, I learned a lot from her teaching. When the class was over, I asked where I could take more of her classes. She said she taught in the Sculpture Department, so I started taking sculpture classes.

What made me continue to be interested in sculpture back then overlaps some of the things I still find interesting about it today. Sculpture offers an artist plethora of problems. Some of these are obvious, such a material choices and how to deal with those materials in gravity. But many problems are underlying, such as how to navigate through a three-dimensional form, how to coax a viewer into wanting to look at work to generate meaning. Because a sculpture can be made from wood, steel, plastic, performance, space, light, audio, it makes the “conceptual net” its material ground. This offers much possibility and diversity. To navigate this ever changing ground asks a sculptor to be a very present and very creative problem solver. This was and is extremely interesting to me.

What made me continue to be interested in sculpture back then overlaps some of the things I still find interesting about it today. Sculpture offers an artist plethora of problems. Some of these are obvious, such a material choices and how to deal with those materials in gravity. But many problems are underlying, such as how to navigate through a three-dimensional form, how to coax a viewer into wanting to look at work to generate meaning. Because a sculpture can be made from wood, steel, plastic, performance, space, light, audio, it makes the “conceptual net” its material ground. This offers much possibility and diversity. To navigate this ever changing ground asks a sculptor to be a very present and very creative problem solver. This was and is extremely interesting to me.

Where does the inspiration for your projects come from?

Referentially, I look at moments in art history that show an overlap or archetypal resonance to things that occur today in our pop culture, so mythology, fairytales, advertising, and film are places I look toward seeing how meaning is generated toward a public. As for the mechanics, or how the work “performs’ in a space, I am greatly inspired by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and also by how one’s eyes takes in information from a space or around a curve (meaning, the optical tricks we do to synthesize color and shapes into a whole for seemingly better recognition). I use all of these references as cues on how to build a sculpture in space that seems as if it is evolving within its own 360 degrees.

My barometer to gauge how this may be working is to see responses from people who are knowledgeable in the field of fine art, but also instinctive responses from people who have no knowledge of where the references are coming from but are attracted to it formally. As such, the responses and wonderment of my mother and family are also great inspirations to me. I want them to look at it and simply say, “Wow, that is really cool!”

What do you do when you’re frustrated with a piece you’re working on and you can’t seem to make it the way you want?

This is another great question. Every artist needs to deal with the moment when stagnation comes into the studio and how to effectively manage it. Depending on the piece, and what it is that may be frustrating me about it, I do different things. These mostly relate to getting outside of my own head, so I can “see” the work for what it is at the present moment more clearly.

This is another great question. Every artist needs to deal with the moment when stagnation comes into the studio and how to effectively manage it. Depending on the piece, and what it is that may be frustrating me about it, I do different things. These mostly relate to getting outside of my own head, so I can “see” the work for what it is at the present moment more clearly.

Sometimes, I work on another sculpture. Sometimes, I photograph the work and cut up that photo and reposition its parts. Sometimes, I look at the form and ask what is essential to its composition, and then remove what is not necessary. Sometimes, I instinctively grab a saw-zall and begin sawing it apart! Nothing is precious in my studio.

It’s important that my work is built within a plastic mindset, so I encourage change often. This helps me get “stuck” less often.

Why do you want the viewers of your artwork to have an emotional connection with what they are seeing?

It’s important to me that a viewer is a collaborator in generating meaning in my work. I do that by obscuring many of the forms, by making some parts in a very high resolution, while others are abstract.

I am less interested in any one person “getting” my references or thinking that they should know what the work means, than I am in each person having an individualized experience with the work. For this to truly happen, I believe a viewer needs to feel some investment in that experience. The best way I can do get that reward for the time they take to look is to have it resonate emotionally.

What’s your favorite piece of work that you have done and why?

This is a very hard question, not because I like every work I have done, but because it is very rare that I look at a finished work and don’t think that more improvements should be made upon it.

This is a very hard question, not because I like every work I have done, but because it is very rare that I look at a finished work and don’t think that more improvements should be made upon it.

If I had to choose one, I would say Snowman (2000) is my favorite sculpture to date. I think making this work came at a critical point of my creative development, a point where I began to own my autonomy in my own art-making process vs. feeling I needed to follow a gallery’s instructions.

Snowman is a fairly simple contemplative form. Because it cues a reference that everyone can relate to (the joy of making a snowman), there is an inherent pathos to the work that speaks about fragility and loss, yet the actual sculpture is raised very high and is made from a highly present durable fiberglass. It’s a quiet paradox. One of the editions of Snowman is in the Walker Museum and one is in the Köln Sculpture Park in Köln, Germany.

What do you think has been your biggest accomplishment in your career so far?

Well, I suppose I should list my 2005 Guggenheim Fellowship Award, or the 2010 MacDowell Fellowship Award I just received. Although these are aspects of my career that I am immensely humbled by and also proud of, my biggest accomplishment isn’t tied to an award or a prize of sorts.

I think my biggest accomplishment thus far has been to redirect my creativity so that I feel I am an author of my work’s future in the midst of the system that makes art “work,” which is the art world.

Sometimes, navigating this course has allowed me to receive awards. Although that is nice, overall, I am most happy that I can walk into my studio today and be excited for my sculpture’s future. I am not sure what my future sculptures at will look like, but I am sure I will work my hardest to make it so. I am committed unconditionally to it, and that is my biggest accomplishment for sure.

What is your latest project that you are working on right now?

In February, I will be going to MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire to work on a series of large helium balloons called “Seven.” Each balloon is more than seven feel tall and is jointed like an abstracted figure. Painted on one side of the silver Mylar balloon will be a triad representing one virtue, one vice, and one dwarf (from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs). My goal is to have all seven figures floating in space, where their reflective backsides will reveal aspects of each other.

Helium expands with heat, and as such, when the helium wants to leak out of the Mylar, the balloons will try to reach towards the closest heat source in the room, which will be the exhibition lights. Eventually, the forms will slowly fall to the floor, turning the figures into abstracted folds into the ground. This will literally speak about their progression from one state to another. Metaphorically, it will talk about going from life to death.