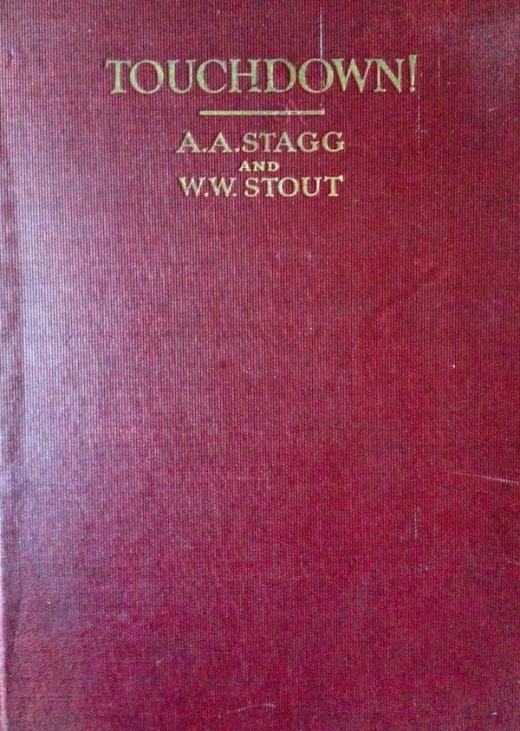

In 1994 I found a $15 edition of “Touchdown” written by Amos Alonzo Stagg in a New Haven used bookstore.

Stagg coached the University of Chicago’s powerhouse teams from 1892 through 1932. (Chicago, a founding member of the Big Ten dropped out of the conference in 1939)

Using what Stagg wrote in 1927, I constructed an “exclusive interview” about today’s college game.

Today’s issues of cheating are not new. In 2013 we’ve seen alumni influence the firing two coaches before the end of September. What do you see being the biggest problem in college football?

“The alumni are now the most active agents in developing athletic immorality, but they not infrequently have cooperation from the authorities of the colleges.”

But don’t colleges have to “cut corners” to be successful on the field?

“It is not necessary to cheat or to buy players in order to produce a team of which a school may be proud. A college with brains and courage does not need to hire a squad of mercenaries to wear its uniform.”

College football faces a credibility issue with a public that may believe every big time college athlete is getting something under the table. In your experience did you find resistance to the game getting “Too Big”?

“The sound of 80,000 or more spectators paying $500,000 or more to see twenty-two college boys play a game for an hour was frightening to some minds. That was too much money, too many persons. Such figures are without precedent, therefore they must be somehow dangerous.”

Given the dangers of big money what do you say about today’s college football donors wielding outsized influence on their school’s programs?

“Someone has said that college football has become so profitable an enterprise financially that it would pay a man, willing to take a chance, to buy a small college outright and operate it as a cloak for his football eleven.”

Given the temptations why do you think universities allow the risks of big-time sports on their campuses?

“For thirty-five years I have listened to faculty members that a student’s choice of college is not governed and infrequently influenced by the athletic prowess of the school. Yet this is demonstrably not true. We all love a winner. Princeton’s Doctor Henry van Dyke testified that he had never heard of Princeton until 1863 when, as a boy in Brooklyn, he saw the Princeton baseball team wallop the Excelsiors of Brooklyn.”

Can you explain the code you expected for your University of Chicago lettermen?

“With the “C” goes a code. A man must be amateur in spirit and in act, disdainful of subterfuge and dishonesty and ashamed to sell his athletic skill. He must be a gentleman and a sportsman, unwilling to win by cheating or unfair tactics. He must train hard and conscientiously and willingly make personal sacrifice to produce the best that is in him, then give it freely and loyally to the university.”

But today athletes know they will be professionals. The temptations of agents, autograph dealers and payouts are so great. What do you say to those who no longer believe in college football’s amateur model?

“Once the college game becomes a nursery for professional gladiators, we shall have to plough up our football fields. The day boys play with one eye on the university and the other on professional futures, the sport will become a moral liability to the colleges.”

The rest of the “interview/book” revealed more interesting stories from Stagg.

In 1927 the Big Ten had a rule keeping any former professional players from coaching their schools.

In the late 1800s some schools fielded teams of men who weren’t even students at their school.

The first “Big Ten Championship Game” was actually played in 1899 between Wisconsin and Chicago. Both teams finished the season undefeated, so to settle things, the teams played in Madison on December 9th with Chicago winning 17-0.

Among the stories it became apparent a strained amateurism existed that remains today. Just as the game grew exponentially then, it is raking in unprecedented money now. That $500,000 gate Stagg mentioned in 1927? Coincidentally it translates to roughly $6.7 million now; about what a big-time college teams makes on a home game in 2013.

What amazes me is how easily Stagg’s answers can describe today’s game. If we study history we see one constant; times change but human nature does not. Some issues from ninety years ago remain, but football has thrived because great leaders carried it across the decades.

I had one last question for Coach Stagg.

Could you tell us about how you started playing football?

“When I was a boy in West Orange, New Jersey, in the years just following the Civil War, my father annually bought two shotes in the early spring and fattened them for November butchering. The meat was salted down in part, the hams smoked and the balance ground into sausage, which, with buckwheat cakes, was our winter breakfast seven mornings a week.

Each year I spoke for the bladders of the slaughtered hogs. These bladders we inflated by blowing through a quill. They were the only footballs we knew, and such usually had been the football as far back as it can be traced”

Thankfully the game ball has improved. Now please pass the pancakes and sausage.