Tucked away in the northern reaches of Penn State’s campus among the agricultural buildings is a level-three biological containment research facility dedicated to learning about – and combating – pathogens affecting both human and animal.

The Eva J. Pell Lab for Advanced Biological Research opened its doors (albeit to a select few people) in 2014. The $23 million facility has all the trappings required for biological containment: redundant systems, water disposal, air scrubbing, layers of security, and strict guidelines for who can and cannot enter the lab space.

Though the Pell Lab is more than 23,000 square feet in total, only about 6,000 is usable lab space. Aside from a small lobby, conference center, and control room, most of the building’s square footage is dedicated to safety and support of the research.

Above the lab are HEPA (high efficiency particulate air) filters to scrub the air before it’s vented outside. The building is kept at a negative air pressure from the outside to ensure nothing escapes. In the basement are tanks where wastewater is cooked before it’s hauled away. Autoclaves are used to heat and sanitize lab equipment. The building is surrounded by a fence and a locked gate, and its location doesn’t show up on a typical Google Maps search.

The Eva J. Pell Lab was a project nearly 15 years in the making, says Dr. Mary Kennett, director of the animal resource program and overseer of animal care.

“Chana Reddy, who was a former director at the Huck Institutes, realized that if we’re going to study diseases that impact humans, and do biomedical research, we need a facility that can safely study these types of agents,” she says.

Much of the funding for the $23 million facility came from a stimulus from the Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, as well as support from the National Institutes of Health.

Its name comes from Penn State’s former senior vice president for research and dean of the graduate school, Eva J. Pell. She went on to work as the undersecretary of science for the Smithsonian Institute before her retirement in 2014. The science administrator was responsible for increasing research expenditures at Penn State from $393 million in 1999 when she took over the research office to $765 million in 2009.

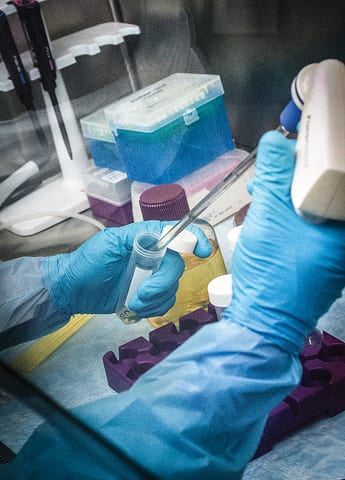

Photo by Patrick Mansell/Penn State

Melissa James, the manager of the Pell Lab, is among the keyholders who ensures that everyone coming into the facility is properly trained according to guidelines set by the Centers for Disease Control.

“There’s a lot of security that goes into the facility itself and access into containment, and only people who are trained and have the proper clearances can enter the biocontainment area,” she says.

Those guidelines are a crucial safety step for the researchers there trying to further humanity’s knowledge of nasty bugs and hopefully figure out better ways to counter them. The lab itself is inspected by the United States Department of Agriculture, CDC, Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and the university’s Animal Care and Use Committee.

Dr. Troy Sutton, assistant professor in veterinary and biomedical sciences, works with viruses inside the containment space. He details the painstaking steps taken by researchers at the lab to protect themselves, which he says is the final step in a building’s safety planning.

“The last design feature in a lab is what we call PPE,” he says. “Which is all of the protective equipment the person wears. So, we engineer in almost all of the safety features in the building, but you still protect the person as well. You enter wearing scrubs. You then wear – at least for my work – a second, disposable Tyvek suit. You then wear an air-purifying respirator over top of that. You then wear at least one more layer over top of that. So, at the point where you’re actually working with an agent, you dispose of that outer layer before you leave the room, before you leave the next room you dispose of another layer, and you’re multiply removing layers until you exit. The last layer you remove prior to getting in the shower is your respirator.”

Dr. Girish Kirimanjeswara is the scientific director of the lab, and studies Bordetella and Francisella tularensis.

There is a practical side to the research at the Pell Lab, as new diseases are always emerging and some treatments don’t work as well as they used to.

“We are more focused on antibiotic-resistant bacteria,” he says about his work. “So, that’s a big problem now, because the existing antibiotics are no longer useful, especially against, say, tuberculosis or MRSA. And then what we do, we try to identify new antibiotics to treat these bacterial diseases, and also try to come up with vaccines, without using antibiotics, so we can prevent the disease rather than trying to treat the disease.”

Recently at Pell Lab, Dr. Jason Rasgon studied how well Pennsylvania’s mosquitoes carried the Zika virus, a disease that made a huge splash in the news after an outbreak in Brazil in 2015. Fortunately, his research has found so far that local mosquitoes are not good carriers.

This is an example of the melding of public interest with biological research. Like studies of avian influenza, Pennsylvania residents benefit from knowing how its animals and residents will be affected by emerging pathogens.

Kirimanjeswara and Dr. Kenneth Keiler, professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, are credited with discovering compounds to defend against Francisella tularensis. The disease causes tularemia (rabbit fever), and the U.S. government considers it a tier-one select agent for its possible use for bioterrorism, according to a 2016 Penn State News article.

Photo by Patrick Mansell/Penn State

The work at the Pell Lab also aides the health research of agriculture operations. Sutton studies influenza, including avian flu, an important field of study considering the large number of chickens on Pennsylvania farms.

There are more than 1,000 level-three containment facilities in the U.S., many of them also at universities, but few have the space, security, and comfort of the Eva J. Pell Laboratory.

As an article in Laboratory Magazine pointed out, many biocontainment facilities are dark underground “bunkers,” with utilitarian design that takes into account the ease of security when there are no windows.

Not so at the Pell Lab, with natural light in 75 percent of the workspace thanks to special windows that are capable of withstanding the changing air pressure.

“I have worked in a bunker facility,” Kirimanjeswara says. “So, a small, very dingy place where there’s no sunlight. So, yeah, it’s very nice to work in a place where there is natural sunlight and you know what’s going on. Even if it’s snow, at least you know what’s going on outside.”

Sutton says of the four biocontainment facilities he’s worked in, Pell is by far the nicest.

There are four levels of biocontainment facilities, with level-one labs used for studying diseases that have a minimal threat to people. Subsequent levels provide for more security and safety for harsher bugs.

Level-four facilities are used for studying diseases with no known cure and are potentially lethal to those that work on them. There are fewer than 20 such labs in the U.S., according to Laboratory Magazine, and most of those are under government control.

Among the best-known level-four facilities in the U.S. is the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (often shortened as USAMRIID) in Frederick, Maryland, where, among many areas of research, scientists worked to uncover the origins and curiosities of the anthrax sent through the mail in 2001.

The level-four facility at the CDC in Atlanta houses the only known stock of smallpox in the U.S. after the World Health Organization declared the disease eradicated in 1980. The other known stockpile in the world is at the Vector Institute in Russia.

You won’t find smallpox or anthrax at the Pell Lab. Level-three facilities work only with diseases that have a known cure.

Despite the presence of these pathogens, Kirimanjeswara says it is probably the safest place in Centre County because of its state-of-the-art climate and control systems, and layers of security.

“I can paraphrase what my son says: ‘It’s the safest building on earth,’” he says. “If anything happens around Centre County, I would first come and stay here.”

Sean Yoder is a freelance writer who lives in Bellefonte.