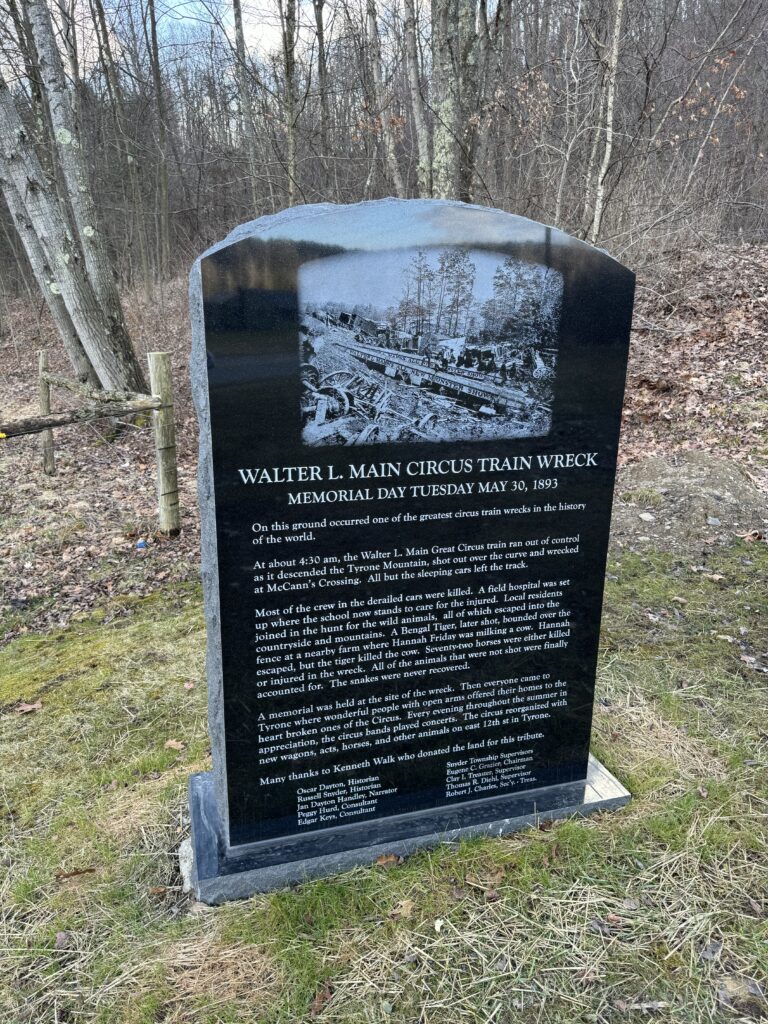

The aftermath of the May 30, 1893, train wreck (Photo courtesy of Local Historia)

The aftermath of the May 30, 1893, train wreck (Photo courtesy of Local Historia)

In the early morning hours of May 30, 1893, Engineer “Red” Cresswell attempted to bring Walter L. Main’s circus train—full of exotic animals, expert performers, employees, equipment and Main himself—down one of the most treacherous stretches of railroad in all of Pennsylvania. Despite his reservations about the ability to control the oversized railcars, pressures from Main, the railroad company and America itself set in motion one of the most infamous railroading disasters of the 19th century.

In 1893, the country was a juxtaposition of technological boom and economic bust. That year, the Chicago World’s Fair dazzled millions, demonstrating wonders like the “moving walkway,” Juicy Fruit gum and life-sized models of the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria celebrating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s journey. At the same time, America was at the onset of an economic crisis. Later to be called the “Panic of 1893,” the severe recession was pervasive throughout American business and society, affecting wealthy merchants and local farmers alike. Many struggled to find steady work and looked to the railroad for help.

Amid such uncertainty, entertainment was at a premium, ushering in the “Golden Age of Circuses.” In the late 1800s, premier traveling shows like Barnum & Bailey, the Ringling Brothers, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and the Walter L. Main Circus provided folks with a way to escape the harsh realities facing their communities. Most shows traveled by rail, putting up their “big tops” near towns and advertising for all to see. In late May 1893, Main’s circus made its way near Centre County.

On May 29, Main’s circus performed in Houtzdale to thousands who traveled from across Centre, Blair and Clearfield counties. The show featured all the trappings that made the Walter L. Main Circus such a massive hit across the country: a menagerie of exotic animals, including several tigers, lions, a gorilla, elephants, hyenas, alligators, small reptiles, zebras, kangaroos, panthers and monkeys; and a full cast of sideshow characters like the Lowande Family, the Larue Brothers, the Iron-Jawed Man, the shortest and tallest man, a sword-swallower, a flame-eater, a mind-reader, a lion-tamer, a bearded lady and even a “wild man.” Most importantly, the show was run by the titular ringmaster himself, Walter Main.

Feats of acrobatics and trapeze, clown antics and animal stunts all led up to the part of the show that made Main’s circus unique: 120 rare white stallions trained to perform death-defying stunts to the roar of the crowd. Houtzdale was treated to a legendary performance, but the show ran late and the circus was behind schedule.

Due for a performance in Blair County the following day, Main’s circus packed onto their 17 custom-built train cars and left Houtzdale for Summit, a staging area before a steep mountain decline with two dangerously sharp curves. Normally en route by midnight, Main’s circus was so delayed that by the time the engineers inspected the train at Summit, it was already 3 a.m.

Cresswell, engineer of the locomotive tasked with bringing the circus train down the roughly hour-long trip into Tyrone, expressed concerns about the weight and length of the custom cars and his ability to brake them. He was so concerned, he felt it necessary to delay further and telegram for a second engine from Tyrone. The eventual response was not what Cresswell had hoped for. In no uncertain terms, he was told to bring the train down, or someone else would be sent who would. The railroad was in no position to waste money sending a second team, Main was in no position to wait and Cresswell was in no position to lose his job. With no other option, Cresswell responded, “All right—I am coming.”

The rest of the story is well known to locals. The cars, overweight and too long, proved Cresswell’s fears. After barely staying on the tracks around the Big Fill Curve just across the Centre County line, the train derailed over a 30-foot embankment at McCann’s Crossing. Of the 17 cars in Main’s circus train, only three remained on the tracks. The disaster claimed the lives of hundreds of animals and six people, and spawned legends of exotic beasts loose in the Pennsylvania wilderness.

In remembrance of this infamous disaster, a memorial had been placed near where the wreck occurred along Vanscoyoc Hollow Road, and another small marker was placed in Grandview Cemetery next to the gravesite of two circus employees. Recently, a new memorial, replacing the old, decaying monument, was placed in the same area to commemorate the disaster and the lives it claimed. When visiting, it’s not hard to imagine what occurred on that very spot 131 years before and the pressures and failures that caused such a tragedy. T&G

Local Historia is a passion for local history, community, and preservation. Its mission is to connect you with local history through engaging content and walking tours. Local Historia is owned by public historians Matt Maris and Dustin Elder, who co-author this column. For more, visit localhistoria.com.

Sources:

Richardson, G. (2015, December 4). Banking Panics of the Gilded Age. Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking-panics-of-the-gilded-age

Standiford, L. (2021, June 15). Why the golden age of the American Circus began to fade. Time. https://time.com/6073381/circus-history/

Walter L. Main Circus. Circus and Sideshows. (2013). https://www.circusesandsideshows.com/circuses/walterlmaincircus.html

Zitzler, P., & O’Brien, S. (2008). Unscheduled stop: The Town of Tyrone and the wreck of the Walter L. main circus train. America’s Stories, Inc.

Receive all the latest news and events right to your inbox.

80% of consumers turn to directories with reviews to find a local business.