This story originally appeared in the July 2025 issue of Town&Gown magazine.

The War of 1812 is often overlooked, especially its impact on locals in the middle of Pennsylvania.

In 1811, George Records was one of the first settlers of what is now Worth Township, Centre County. Somewhere between Port Matilda and Julian, he started to clear land to build a home and a life. Meanwhile, on the high seas and upon battlefields far away, trouble brewed between European empires. American sailors were being harassed and impressed into the British Navy. The young United States saw an opportunity to expand into British-held Canada, moving any enemy, including American Indians, out of her way. At the urging of President James Madison, Congress declared war on Great Britain in June of 1812. George Records was drafted for six months into the Pennsylvania Militia. His homebuilding would have to wait; Captain Records would raise a company instead and march them to Lake Erie.

It’s difficult to imagine what it would be like to march to Erie from Centre County during the summer of 1813. Records and his company rendezvoused and joined with Colonel Rees Hill’s Regiment, assigned to protect Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s fleet at Presque Isle. The duty-bound men in Records’ company included a hatter from Aaronsburg, a tide-pilot from Howard, an ironworker from Benner’s Forge, blacksmiths, cabinet-makers, farmers, tailors, and a saddler from Bellefonte. Many didn’t have much, so after the Army failed to pay the regiment for a couple months, the officers and men refused to obey marching orders to relocate to Ohio to join the Army of the Northwest under future president General William Henry Harrison. This protest took a fateful turn, perhaps stalling them just enough to remain at Presque Isle until Perry’s squadron was ready for battle.

While Perry’s ships were constructed, armed, and manned, British warships lurked outside the bay. Other than a spy or two who were discovered, the militia’s presence seemed to prevent any interference from the British or their Native American allies. At one point, perhaps prompted by boredom or on a scouting mission, a detail including Captain Records and a small group of men ventured a few miles outside of Erie, where they encountered an old “Indian Burial Ground.” Some of the men desecrated graves and collected trophies to take home. Although it was a time of war, such disregard for a burial ground is quite symbolic of the war’s impact on Indigenous Peoples in North America. While the British and Americans focused on their own plans for the continent, it was American Indians who lost the most.

When Commodore Perry’s ships were finally ready, many of his sailors were not, and they remained unfit for duty on the sick list. Under the circumstances, the Harrisburg Chronicle reported in August of 1813 that “volunteers have been invited to serve on board the vessels of war in this port, until the enemy is conquered. … Many of the most respectable young men in Colonel Hill’s Regiment have turned out.” Ironically, the Centre County men who volunteered had not even been paid for their service at that point.

Among the “landsmen” who did volunteer from Centre County were John Lucas and John Silhammer (aka Sythammer). A famed hunter from Snow Shoe named Samuel Askey also attempted to volunteer, but Perry would not allow him because he was married. Lucas, Silhammer, and others would forever join the annals of American naval history on Sept. 10, 1813, at the Battle of Lake Erie.

Perry was ready to pursue the enemy and evict them from the Great Lake, gaining both glory and control of a major supply line. The volunteers were inspected like the rest of the men by Commodore Perry and took on the role of marines where needed. The sailors welcomed the “gallant boys from the Keystone State.” Lucas served on the schooner Ariel. Silhammer was on board the schooner Scorpion. Guns were inspected, a ration of grog was issued, and sand was sprinkled on the decks in preparation for the blood that was sure to spill. “All hands, all hands, all hands, to quarters.” From his flagship, the USS Lawrence, Commodore Perry exclaimed, “My brave lads, this flag contains the last words of the brave Capt. Lawrence. Shall I hoist it?” From all quarters came the response “aye, aye.” Perry raised his famous “don’t give up the ship” flag amid the cheers of his men.

As Perry’s flotilla of nine ships chased down the British fleet near Put-in-Bay, Ohio, the Scorpion fired the first shot with its long-range gun. Many know the epic saga that ensued, with Perry taking a small boat from the battered flagship in order to complete his great victory aboard the brig USS Niagara. Perry captured an entire British squadron and famously reported, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” Master Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry and his men, including local landsmen from Centre County, achieved an unprecedented victory against the most powerful navy in the world.

The butcher’s bill, as they say, is that Perry’s fleet suffered 123 casualties, with 27 killed (96 wounded). The British suffered about 440 casualties. John Lucas was wounded in the foot when a cannon-carriage rolled over it aboard the Ariel. Unfortunately, John Silhammer was killed in action aboard the Scorpion. Three American and three British officers were buried together on shore. But the enlisted men like John Silhammer were lashed into their hammocks, weighted with cannonballs, and buried in the “watery grave” of Lake Erie.

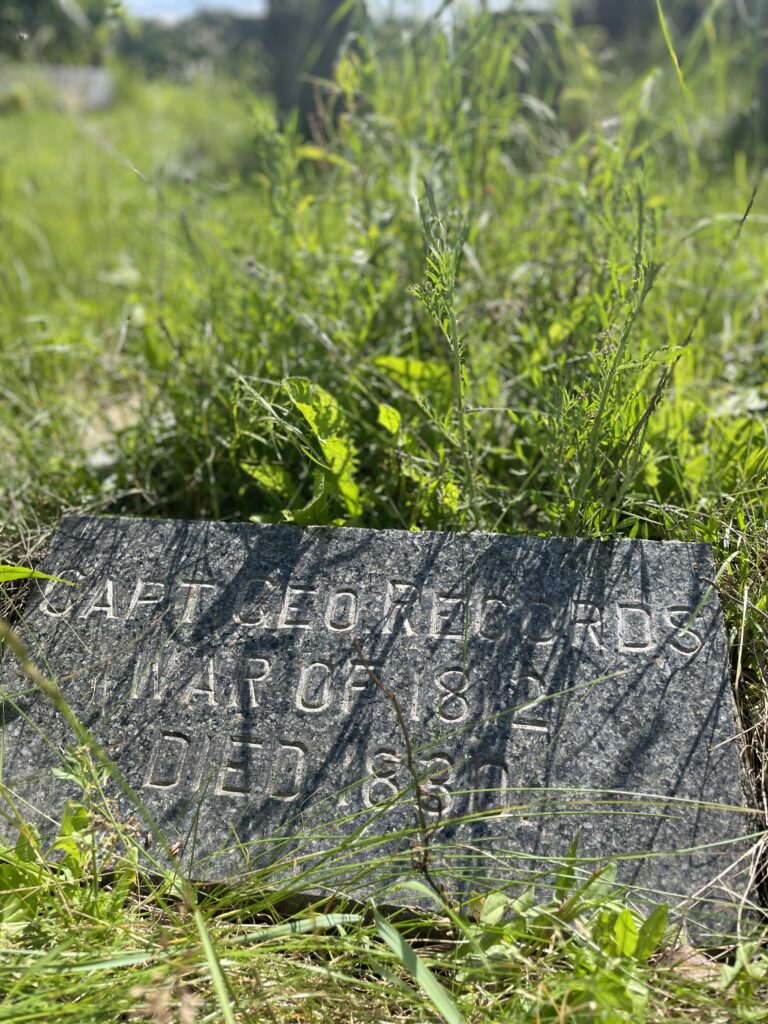

George Records finished his service in Ohio under General Harrison. He eventually returned to his homestead in Centre County. Never having received any pay, he petitioned the paymaster. In 1814, he wrote, “We can’t afford to serve the United States for nothing.” It is uncertain whether he or the rest of his company were paid, but the handful of locals like John Lucas (who would afterwards be known as “Perry John Lucas”), William Wagner, William P. Brady, Alexander McCloskey (aboard the Tigress), and others received government issued medals to commemorate their “Patriotism and Bravery in the Naval Action on Lake Erie.” Records is buried in Brown’s Cemetery in Worth Township.

As for landsman John Silhammer, a young saddle-maker from Bellefonte, he paid the ultimate price, and is sleeping among heroes forever in Erie’s watery bed. T&G

Local Historia is a passion for local history, community, and preservation. Its mission is to connect you with local history through engaging content and walking tours. Local Historia is owned by public historians Matt Maris and Dustin Elder, who co-author this column. For more, visit localhistoria.com.

Sources:

Sources:

“Battle of Lake Erie.” National Park Service. Last updated Sept. 30, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/pevi/learn/historyculture/battle_erie_detail.htm

Dobbins, W. W. , 1800?-1877. History of the battle of Lake Erie , and reminiscences of the flagship “Lawrence,”. Erie, Pa., Ashby & Vincent, printers, 1876. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/02017373/.

“From the National Intelligencer.” Lancaster Intelligencer (Lancaster PA). Oct. 2, 1813.

Harrisburg Chronicle (Harrisburg PA). August 9, 1813.

Linn, John B. History of Centre, and Clinton Counties. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1883. https://archive.org/details/historyofcentrec00linn/page/50/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater&q=%22George+Records%22

Parsons, Usher. Battle of Lake Erie. A discourse, delivered before the Rhode-Island historical society, on the evening of Monday, .By Usher Parsons. Providence, B. T. Albro, printer, 1853. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/02017684/

Pennsylvania archives ser.6, v.7.1907. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/njp.32101077282752

Pennsylvania archives ser.6 v.9, 1907. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x004914255

Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette (Pittsburgh PA). Sept. 10, 1813.

Powell, William Henry, Artist, Copyright Claimant Detroit Publishing Co, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co, Jackson, William Henry, photographer. Battle of Lake Erie, by Powell, in the capitol at Washington. Erie, Lake Lake United States Erie, ca. 1902. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016800588/.