This column originally appeared in the September 2025 issue of Town&Gown magazine.

This day I confess to my sorrow and shame,

I shot Reuben Guild whom I never knew by name.

And left his body weltering all in a purple gore,

Even now I regret it and will forever more.[1]

–Ballad of James Munks

(one of many versions)

One of the challenging but enjoyable aspects of being a historian is taking on the role of an investigator. Especially when you are researching a true crime topic, it feels even more like detective work. When approaching a historical topic, sometimes it’s clouded with rumors, exaggerations and misinformation. Tracking down the evidence in local archives, special collections and court records, sleuthing through online newspapers, taking photos of an execution site—it feels like working a case.

Original sources become your best witnesses; each piece of evidence is part of the larger puzzle. As the bigger picture comes into view, we go back into the past, a window into what the world was like, who people were, what they believed and how they lived and died.

James Munks probably would not have made the history books had it not been for an infamous crime, subsequent confession and very public execution. Nor would his name evoke such mystery if paranormal claims had not been published about him escaping the grave and even being resurrected.

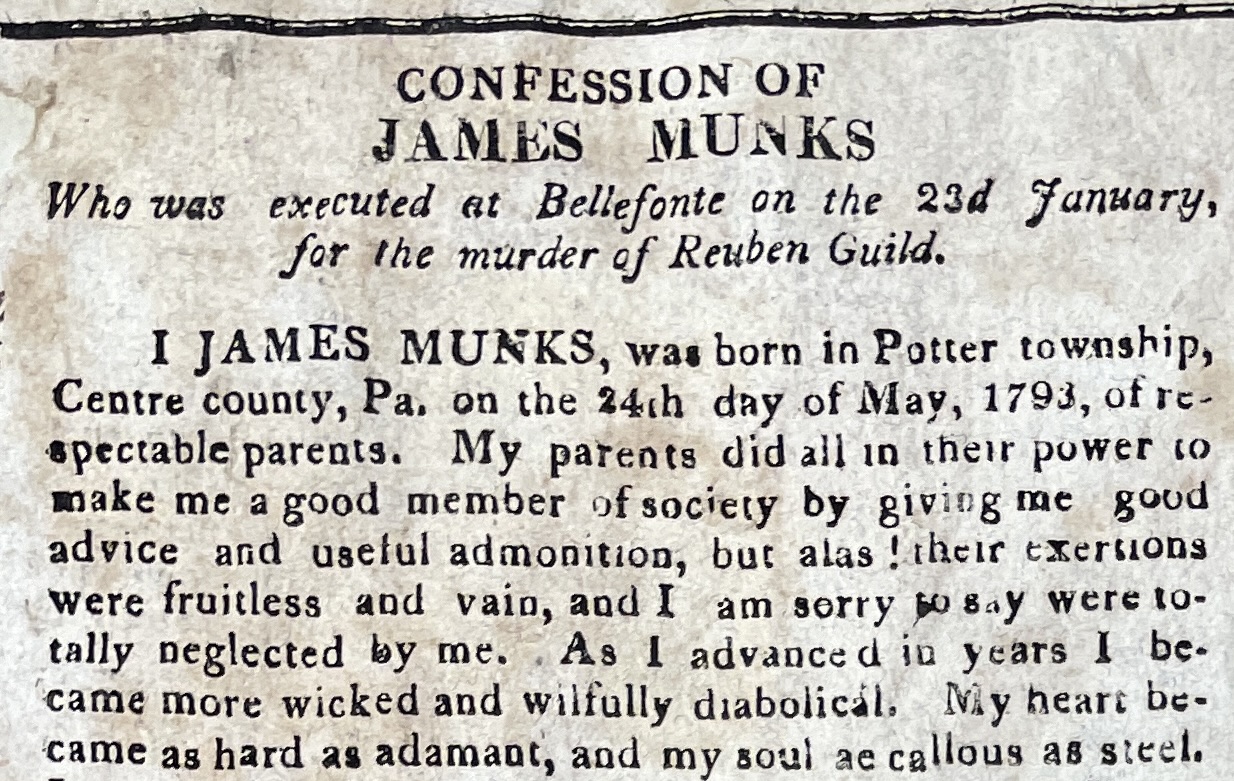

James Munks (sometimes spelled Monks) was born in Potter Township in 1793. So when he committed murder in 1817, he was about 24 years old. There is a strong historical paper trail about his crime because Munks wrote a jailhouse confession about it. While confessions were not always authentic, criminal confessions were a common practice in those days. People have always been fascinated by crime and punishment. Confessions back then were today’s version of true crime shows. The confessions usually included biographical information, the nature of the crime and a religious message warning others not to fall down the same path. The more notorious the criminal or crime, the better.

In researching James Munks, my first question was whether an original copy of Munks’ confession existed. My second question was whether his confession was actually authentic. The confession of James Munks is indeed the real deal. It can be found in Penn State’s special collections, dating back to the time of his execution in 1819. However, the person who saved it forgot to save the small section of the second page of the document. Luckily, because Munks’ story was so popular, various publishers made it into pamphlets to sell, so I was able to find a complete copy of his confession in Princeton University’s special collections. They were nice enough to send me a copy.

The detailed confession exists! In addition, its authenticity was signed off by the Rev. James Linn, jailer Joseph Williams and coroner James MaGee when it was published. In the body of the confession, Munks made it clear that he wanted the proceeds from its sale (at his execution and afterwards) to benefit his soon-to-be-orphaned family, especially the two children he would leave behind. Munks also provided the details of his crime.

On the night of Nov. 16, 1817, according to Munks’ own account, he was at Wrigley’s Tavern in Clearfield County below Anderson Creek. Munks and a few friends drank heavily late into the night. Munks’ intemperance, he confessed, was his downfall and he warned against the “immoderate use of the ardent spirits” which was the “source of sin and the foundation of iniquity.” Munks left Wrigley’s and started to stumble toward his home on Marsh Creek in Howard Township. He didn’t get far when he crossed paths with Reuben Guild (sometimes spelled Giles and Guiles). Guild was a long way from home in Hunterdon, New Jersey, and was traveling to see family in Ohio. As the two men passed each other, they “bid each other good evening.” Then something came over James Munks. He thought, “I must kill that man.” There was no one around to stop the dreadful waylay. Munks raised his rifle and shot Reuben through his back, the bullet coming out his chest.

Reuben Guild fell off of his horse. Munks approached the dying man, who looked up at his assailant and cried, “My friend, you have killed me.” As Guild lay dying on the lonely road, Munks retrieved the riderless horse. Munks tied the horse to a bush and returned to Guild, who appeared to be dead. However, Munks recalled, “fearing that he might not be dead, I took my tomahawk and struck him on the head twice.”

Munks dragged Guild off the road and tried to hide his body beneath roots from a blown-over tree. Munks took the victim’s pocket watch and pocketbook, and even stripped him of his clothes and shoes. It would snow that night, and Munks put on Guild’s great coat, which had a bullet hole in the back. Munks was still intoxicated, though, and did not realize that he had accidentally dropped at the crime scene his own songbook, which, according to the Huntingdon Gazette, “led, in a great measure to his detection.” Munks stuffed the bloody spoils into the saddle bags of his newly acquired horse and headed down the road.

Weeks and months passed. Word had spread its way to the courthouse in Bellefonte. Guild was missing, and folks across Clearfield and Centre counties believed Munks had something to do with it. Sheriff William Alexander kept a close eye on the whereabouts of Munks until he secured a warrant for his arrest. In early May of 1818, Alexander arrested Munks “and without any assistance brought his prisoner many miles on horseback during a dark and rainy night to Bellefonte.”[2]

Meanwhile, a party including Reuben Guild’s son arrived and searched for his missing father. With the help of a dog,[3] they found a bloody shirt that Munks had discarded as well as human bones near Wrigley’s Tavern. Because of this break in the case, the coroner and other witnesses exhumed the body of Reuben Guild while conducting an inquisition on May 22, 1818.

A coroner’s inquisition is a judicial investigation into a suspicious death. I accessed this original document through the Centre County prothonotary, who helped me get a copy. Among other details, it stated the following:

“Inquisition indented and taken in the County of Clearfield … upon the view of part of the bones of a human body found half a mile from [widow] Wrigley’s Tavern and about eighty yards from the state road leading from Bellefonte to Erie. … Presume from the evidence before them that the bones which were found to be the bones of Reuben Guild state of New Jersey Hunterdon County and they likewise presume the felon to be James Munks now in the Goal [jail] of Bellefonte Centre County.”

It’s interesting that the crime occurred in Clearfield County but the trial was held in Centre County. While Clearfield County was formed in 1804, it still shared a judicial district with Centre County until about 1822. Shortly after the remains of Reuben Guild were discovered, Munks was arraigned and indicted for first-degree murder in August 1818. Munks pleaded not guilty, and the stage was set for the ensuing courtroom drama.

Now that we’ve covered the background of the crime and research methods, please stay tuned for the trial, public hanging and alleged resurrection of James Munks. Part 2 of this story takes a spooky turn and will appear in the October issue of Town&Gown. T&G

Local Historia is a passion for local history, community and preservation. Its mission is to connect you with local history through engaging content and walking tours. Local Historia is owned by public historians Matt Maris and Dustin Elder, who co-author this column. For more, visit localhistoria.com.

[1] Democratic Watchman (Bellefonte, Pa.). March 12, 1897.

[2] JBL p. 174 https://archive.org/details/historyofcentrec00linn/page/174/mode/2up

[3] https://www.newspapers.com/image/1001063487/

Sources:

Confession of James Munks held at Princeton Special Collections (Firestone Library). Published by Aaron Guest (Newark, NJ), 1847.

Democratic Watchman (Bellefonte, Pa.). March 12, 1897. Link

Huntingdon Gazette (Huntingdon, Pa). January 28, 1819. Link

Linn, J. Blair., Mitchell, J. Thomas. (1883). History of Centre and Clinton Counties, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts. P. 174. Link

Sykesville-Post Dispatch (Sykesville, Pa). Dec. 1, 1905. Link